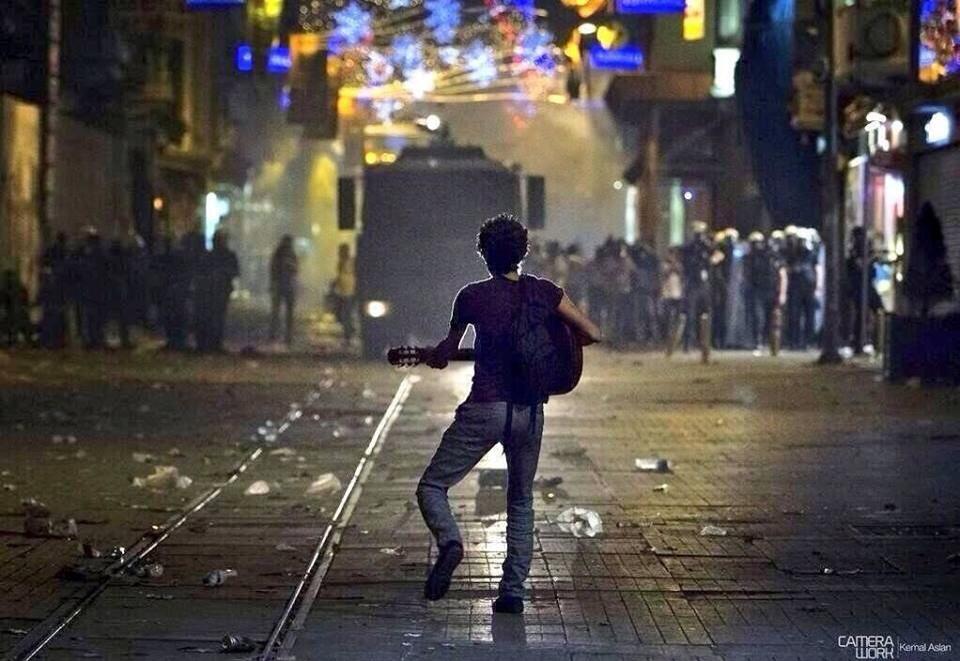

One thing that is necessary for productive conflict transformation is a fairly even playing field when it comes to human rights and access to basic needs. It is unlikely collaborative musicking under these conditions would generate positive shared new identities that lessen tension and prejudice. Under these unequal circumstances, such as in Turkey at the moment, those with less power have the express need to band together, maintain courage and express their own joint identities in the face of oppression. Under these circumstances the usual rules of music and conflict transformation as researched thus far do not apply until the balance of power becomes more even. Until such time, the oppressed have been using music as representation and memory triggers as demonstrated in the below clips. Analysis to come later.

Thursday, 6 June 2013

Music Above Fighting

As with most music and conflict transformation initiatives that I come across, I was excited when I started watching the mini-documentary Music Above Fighting. Based in three conflicted areas separated physically by walls or partitions (Northern Ireland, Israel/Palestine, India/Pakistan), the documentary shows musicians on either side playing with each other across the border. There was one line in particular from an elderly tabla player on the Indian/Pakistani border that struck me: "Only in death and music can I cross the border." I thought this had real potential. I was very disappointed to then discover that they were all just singing and playing "Imagine" by John Lennon. I don't have anything against the song exactly, but songs for peace don't actually change anything. Increased dialogue through music across physical barriers, in spite of the barriers, no that would be inspiring. A missed opportunity.

Long Time - The State of Things in Music and Conflict Transformation

It has been a very long time since I posted anything on this blog, for which I am mightily sorry. I have not been idle, though. I have finally submitted my PhD thesis entitled "Singing to be Normal: Tracing the Behavioural Influence of Music as Conflict Transformation" and I will complete my viva in August. I have an article under review in Poetics, I'm co-authoring/co-editing a book with Olivier Urbain from the Toda Institute entitled Music, Power and Liberty, and I am now an editor and journal manager of the Music and the Arts in Action Journal. I have a couple of conference presentations coming up, including "Protests as Events/Events as Protests" at Leeds Metropolitan University and the European Sociological Association Arts Branch conference in Turin. I have been spending the rest of my time applying for jobs or trying to create my own. Hopefully something will materialise before I starve.

So what has the world been up to since my last post? What follows are some things that have caught my attention:

In Jamaica and other hurricane prone Caribbean countries, poverty and a lack of opportunities has led many men to become involved in crime and violence. Recently, Catholic Relief Services have started the Youth Emergency Action Committee with the help of USAid in order to refocus youth attention on how to best respond to hurricanes and help their communities. They have discovered that the most successful manner in which to do this is through rap music in what they labelled 'edutainment.' This approach has also been used successfully for sex and AIDS education in Ghana. What seems to be happening here is not directly the result of the music, but music that appeals or resonates with a particular group promotes a more attentive mode of attention where messages located in the lyrics may infiltrate into memory, especially if the experience is enjoyed and repeated.

Cambodia Living Arts is an organisation founded by Arn-Chorn Pond, a musician, former child soldier and survivor of the Khmer Rouge genocide. The principles behind the organisation suggest that the arts are needed in order to restore identity, pride and hope to the population. This is particularly remarkable in Cambodia where, according to the Huffington Post, up to 90% of artists were killed. As in other dictatorships, despots are often the first to understand the power of music and the arts. In order to control a population in order to commit atrocities, the victims need to be seen as less than human. This is impossible if the victims are engaged with cultural expression which is the ultimate humanising activity. Despite this fact, aid agencies rarely support cultural activities. This has been criticised by research conducted by the Post-conflict Reconstruction and Development Unit at the University of York as well as by the popular press like the Huffington Post. As a result, Cambodia Living Arts has produced a month-long arts festival in New York called Season of Camboda, with the support from various American philanthropists in order to raise awareness. The localised use of music in this case is the real music and conflict transformation work, yet that is not what is seen in the festival. The festival is an advertisement and fund-raiser, yet that is what audiences will remember. They will also remember a spectacle of sorts that represents a culture they are probably less familiar with. the danger here is that music and the arts is still seen as entertainment or representing a culture that is somehow rarefied, separate and unknowable. Hopefully the festival has been successful in raising awareness and funds for the important work that they do in their own communities. I hope that their work is not commodified too much in the process.

That's probably enough for this post.

So what has the world been up to since my last post? What follows are some things that have caught my attention:

In Jamaica and other hurricane prone Caribbean countries, poverty and a lack of opportunities has led many men to become involved in crime and violence. Recently, Catholic Relief Services have started the Youth Emergency Action Committee with the help of USAid in order to refocus youth attention on how to best respond to hurricanes and help their communities. They have discovered that the most successful manner in which to do this is through rap music in what they labelled 'edutainment.' This approach has also been used successfully for sex and AIDS education in Ghana. What seems to be happening here is not directly the result of the music, but music that appeals or resonates with a particular group promotes a more attentive mode of attention where messages located in the lyrics may infiltrate into memory, especially if the experience is enjoyed and repeated.

Cambodia Living Arts is an organisation founded by Arn-Chorn Pond, a musician, former child soldier and survivor of the Khmer Rouge genocide. The principles behind the organisation suggest that the arts are needed in order to restore identity, pride and hope to the population. This is particularly remarkable in Cambodia where, according to the Huffington Post, up to 90% of artists were killed. As in other dictatorships, despots are often the first to understand the power of music and the arts. In order to control a population in order to commit atrocities, the victims need to be seen as less than human. This is impossible if the victims are engaged with cultural expression which is the ultimate humanising activity. Despite this fact, aid agencies rarely support cultural activities. This has been criticised by research conducted by the Post-conflict Reconstruction and Development Unit at the University of York as well as by the popular press like the Huffington Post. As a result, Cambodia Living Arts has produced a month-long arts festival in New York called Season of Camboda, with the support from various American philanthropists in order to raise awareness. The localised use of music in this case is the real music and conflict transformation work, yet that is not what is seen in the festival. The festival is an advertisement and fund-raiser, yet that is what audiences will remember. They will also remember a spectacle of sorts that represents a culture they are probably less familiar with. the danger here is that music and the arts is still seen as entertainment or representing a culture that is somehow rarefied, separate and unknowable. Hopefully the festival has been successful in raising awareness and funds for the important work that they do in their own communities. I hope that their work is not commodified too much in the process.

That's probably enough for this post.

Labels:

arts,

awareness,

Cambodia,

conflict transformation,

Culture,

education,

identity,

Jamaica,

music,

pride,

rap,

representation

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)